Tier 1 Ocean Heat Content

Synthesis

Related diagnostics

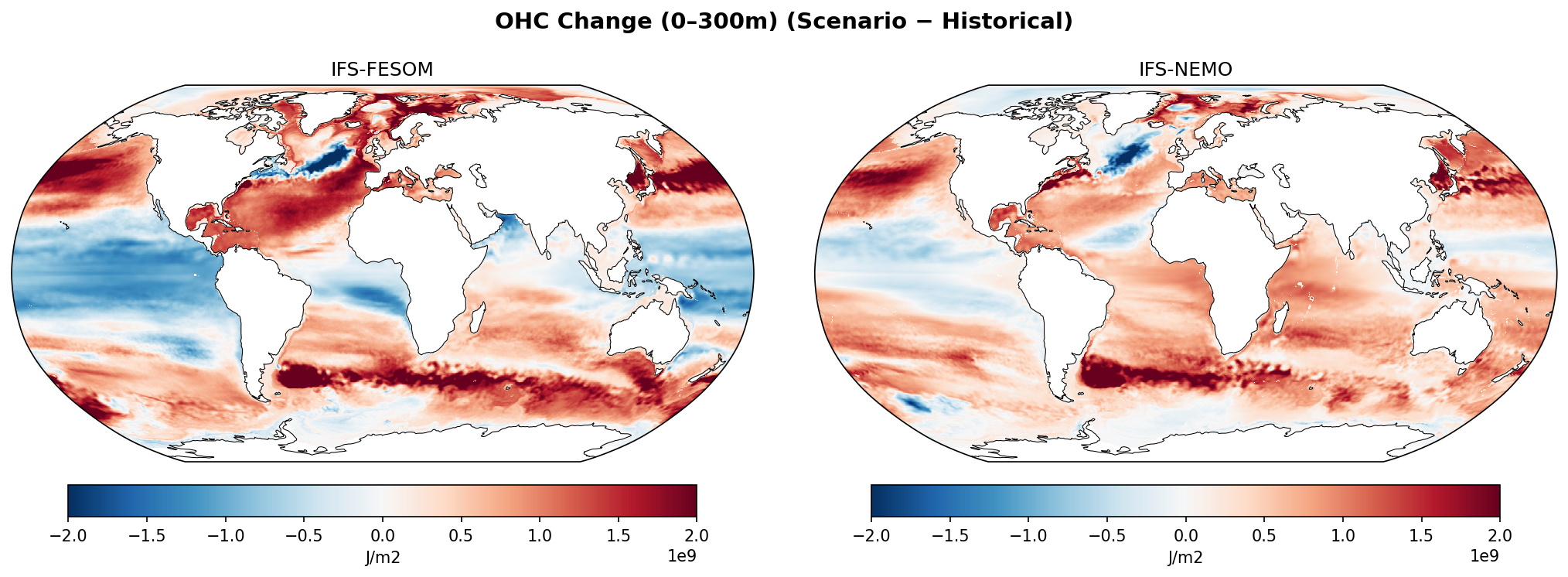

OHC Change (0–300m)

| Variables | avg_hc300m |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | J/m2 |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | Future mean minus historical mean. |

Summary medium

The figure illustrates the projected change in upper-ocean heat content (0–300m) between 1990–2014 and 2040–2049 under SSP3-7.0 for IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO, revealing a dominant global warming signal punctuated by distinct cooling regions in the North Atlantic and equatorial Pacific.

Key Findings

- Both models exhibit a prominent 'warming hole' (negative OHC change) in the subpolar North Atlantic, consistent with AMOC weakening.

- IFS-FESOM projects a significantly broader and more intense region of cooling in the equatorial and tropical Pacific compared to the mixed signal in IFS-NEMO.

- Western Boundary Current extensions (Gulf Stream, Kuroshio) and the Agulhas Retroflection show the highest magnitudes of heat accumulation (> 2 × 10^9 J/m²).

Spatial Patterns

Globally, the background state is warming, particularly in the subtropical gyres and Southern Ocean frontal zones. A strong dipole exists in the North Atlantic with subpolar cooling contrasted against intense warming in the Gulf Stream extension. In the Southern Hemisphere, a distinct high-warming band aligns with the Agulhas Return Current and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) path.

Model Agreement

There is strong structural agreement on the North Atlantic subpolar cooling and the intensification of heat content in Western Boundary Current extensions. However, the models diverge significantly in the tropical Pacific; IFS-FESOM displays a basin-wide La Niña-like cooling pattern, whereas IFS-NEMO shows a weaker, more confined cooling tongue in the east with warming in the west. IFS-FESOM also resolves sharper, more intense warming features in the Agulhas region.

Physical Interpretation

The North Atlantic cooling is a characteristic fingerprint of a slowing Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) reducing northward heat transport. The intense warming in boundary currents suggests a poleward shift or intensification of these systems. The cooling in the tropical Pacific (particularly in FESOM) may result from a dynamical thermostat mechanism (stronger upwelling) or merely reflect internal decadal variability (e.g., a negative IPO/ENSO phase) captured within the short 10-year future averaging window.

Caveats

- The future averaging period is short (10 years: 2040–2049), meaning internal variability (e.g., ENSO phases) may dominate the climate change signal, particularly in the tropical Pacific.

- Analysis is limited to the upper 300m; significant heat uptake occurs at greater depths, especially in the Southern Ocean, which is not captured here.

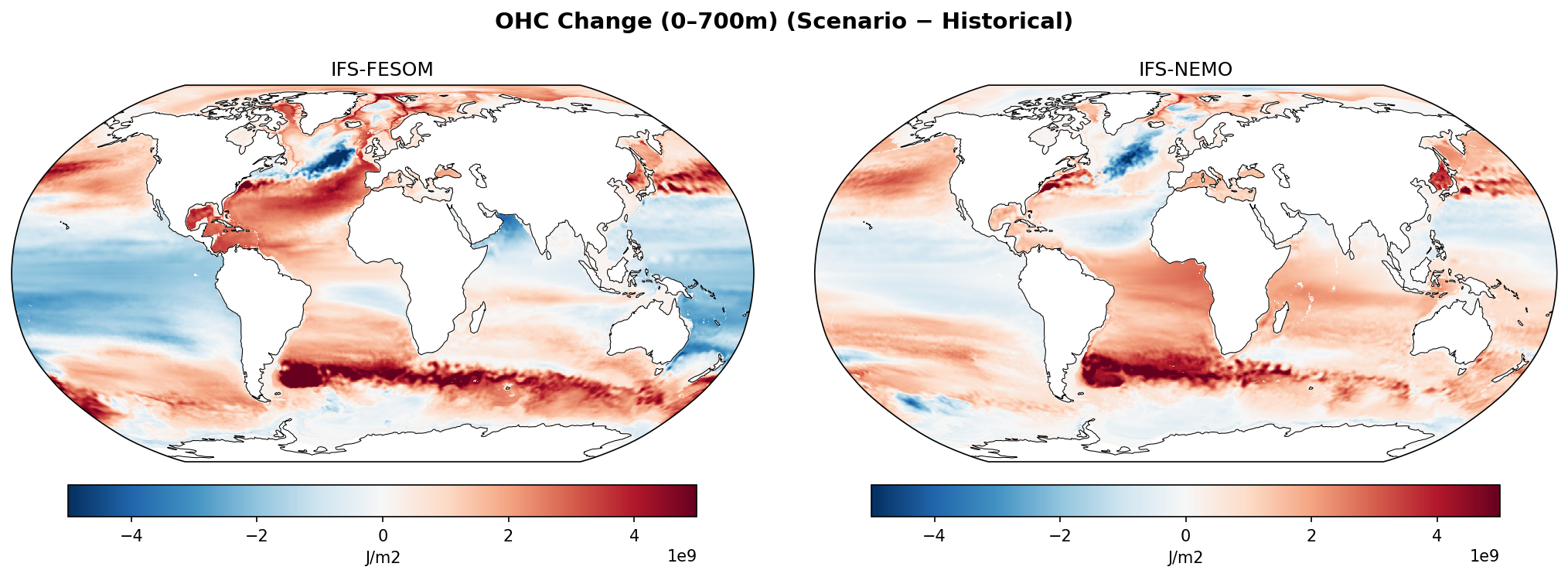

OHC Change (0–700m)

| Variables | avg_hc700m |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | J/m2 |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | Future mean minus historical mean. |

Summary high

The figure illustrates upper-ocean (0–700m) heat content changes between 2040–2049 and 1990–2014 under SSP3-7.0, revealing a globally heterogeneous pattern dominated by Western Boundary Current warming and a North Atlantic cooling signal.

Key Findings

- Both models exhibit a prominent 'warming hole' (cooling > -4e9 J/m²) in the North Atlantic subpolar gyre, consistent with AMOC slowdown.

- Intense heat accumulation (> 4e9 J/m²) is concentrated in the extensions of Western Boundary Currents (Gulf Stream, Kuroshio, Brazil-Malvinas) and the Southern Ocean sector of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

- A notable divergence exists in the Pacific basin: IFS-FESOM projects widespread cooling in the North and Eastern Tropical Pacific, whereas IFS-NEMO indicates largely neutral to warming conditions in the North Pacific.

Spatial Patterns

The maps display a distinct dipole in the North Atlantic with warming in the Gulf Stream extension and cooling south of Greenland. In the Southern Hemisphere, a zonal band of high heat uptake aligns with the Agulhas Return Current and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The tropical Pacific in IFS-FESOM shows a La Niña-like cooling pattern in the east, which is much weaker or absent in IFS-NEMO.

Model Agreement

There is strong structural agreement on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) fingerprint and Southern Ocean heat uptake mechanisms. Disagreement is most pronounced in the Pacific, likely due to differing resolutions or parameterizations of tropical dynamics and mixing schemes between the unstructured grid (FESOM) and structured grid (NEMO) ocean components.

Physical Interpretation

The North Atlantic cooling signals reduced northward heat transport due to a likely weakening AMOC. The warming in Western Boundary Currents suggests a poleward shift and intensification of these systems. Southern Ocean warming reflects enhanced heat uptake via wind-driven subduction and eddy mixing in high-energy regions. The Pacific discrepancy suggests different model sensitivities to the 'ocean dynamical thermostat' mechanism versus atmospheric thermodynamic forcing.

Caveats

- The analysis compares a single future decadal mean (2040-2049) against history, meaning internal decadal variability could impose noise on the forced signal.

- Differences in grid topology (unstructured FESOM vs. tripolar NEMO) may influence effective resolution and diffusion in key regions like boundary currents.

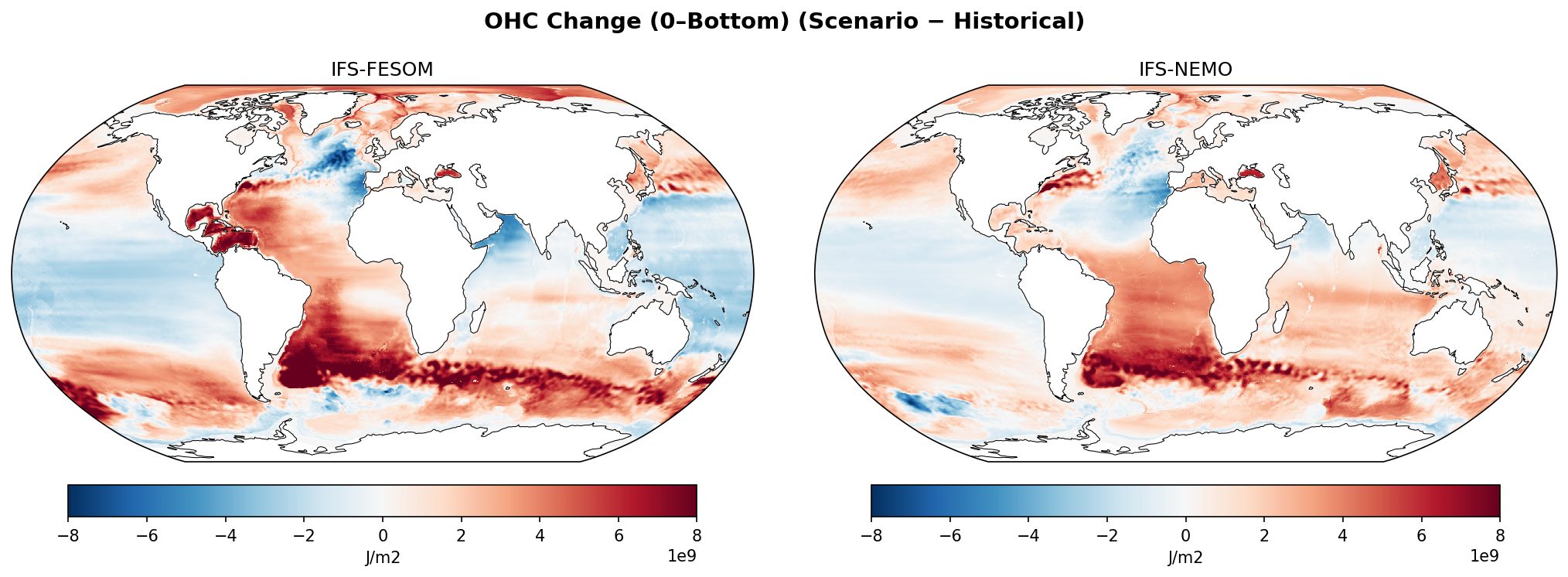

OHC Change (0–Bottom)

| Variables | avg_hcbtm |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | J/m2 |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | Future mean minus historical mean. |

Summary high

The figure illustrates the change in vertically integrated ocean heat content (OHC) between the future (2040–2049) and historical (1990–2014) periods under SSP3-7.0 for IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO. Both models exhibit robust heat uptake in the Southern Ocean and western boundary currents, contrasted by a prominent cooling signal in the North Atlantic subpolar gyre.

Key Findings

- A distinct 'North Atlantic Warming Hole' (cooling trend) is visible in the subpolar gyre of both models, indicative of AMOC weakening.

- The Southern Ocean serves as the primary heat sink, with OHC increases exceeding 8 × 10^9 J/m² along the Antarctic Circumpolar Current path, particularly in the Atlantic and Indian sectors.

- Western Boundary Current regions (Gulf Stream and Kuroshio Extension) show intense warming bands, suggesting frontal shifts or intensification.

- IFS-FESOM predicts significantly higher heat accumulation in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and the Argentine Basin compared to IFS-NEMO.

Spatial Patterns

The global pattern is dominated by strong zonal bands of heat uptake in the Southern Hemisphere subtropics and mid-latitudes. In the Northern Hemisphere, the North Atlantic features a sharp dipole: intense warming in the Gulf Stream extension contrasts with cooling south of Greenland. The Pacific shows a more diffuse pattern with weak cooling or neutral trends in the central North Pacific and moderate warming in the subtropics.

Model Agreement

Both models agree on the large-scale sign and location of the major features: the North Atlantic cooling hole, the high Southern Ocean uptake, and the warming in western boundary current extensions. This consistency strengthens confidence in the dynamical response of the coupled systems.

Physical Interpretation

The North Atlantic cooling is a signature fingerprint of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) slowdown, reducing northward heat transport. The intense Southern Ocean heat uptake is driven by wind-driven ventilation and the exposure of deep, old waters to surface warming. High OHC changes in Western Boundary Currents likely reflect poleward shifts of currents and eddy-induced heat transport changes rather than purely thermodynamic surface heating.

Caveats

- The 10-year averaging period (2040–2049) may still contain internal decadal variability (e.g., ENSO, PDO phases) superimposed on the forced climate signal.

- Vertically integrated metrics do not distinguish between surface mixed-layer warming and deep ocean heat storage.