Tier 2 Inter-model Agreement

Synthesis

Related diagnostics

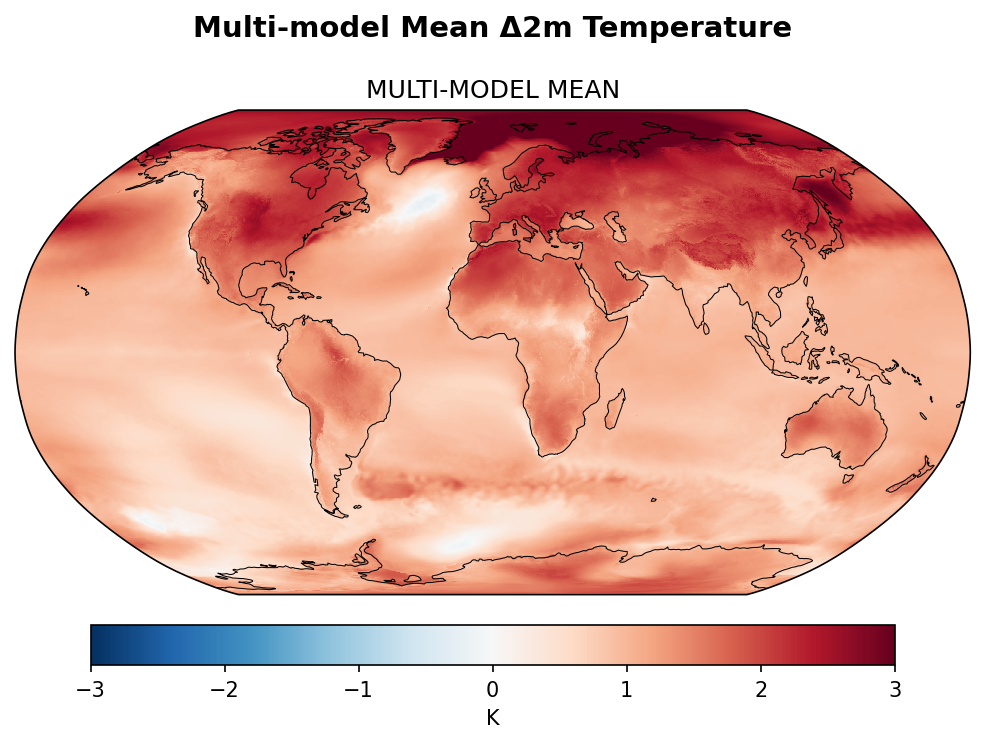

Multi-model Mean 2m Temperature Change

| Variables | avg_2t |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | K |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | Arithmetic mean of per-model (future − historical) differences. |

Summary high

The figure displays the multi-model mean change in 2-meter temperature for the 2040–2049 period relative to the 1990–2014 baseline under the SSP3-7.0 scenario, averaged across the IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO models. The map reveals a robust global warming signal characterized by marked hemispheric asymmetry and distinct regional anomalies.

Key Findings

- Arctic Amplification is the dominant feature, with warming exceeding +2.5 K across the Arctic Ocean, Siberia, and Northern Canada.

- A prominent 'warming hole' is visible in the subpolar North Atlantic, where temperature change is near-neutral or slightly negative (-0.5 K to 0 K).

- Strong land-sea contrast is evident, with continental landmasses generally warming by 1.5–2.5 K, while subtropical ocean basins warm more moderately (0.5–1.0 K).

Spatial Patterns

The Northern Hemisphere shows significantly stronger warming than the Southern Hemisphere. Topographic features, such as the Himalayas and the Andes, exhibit enhanced warming relative to surrounding lowlands. The Southern Ocean shows delayed warming (pale orange), while localized hotspots appear near the Antarctic Peninsula and Weddell Sea.

Model Agreement

Since this is a mean of two closely related models (sharing the IFS atmosphere but differing in ocean discretization: FESOM vs. NEMO), the smooth spatial structures imply high agreement on the large-scale response. The sharp definition of the North Atlantic warming hole suggests both ocean components consistently resolve the dynamic slowdown mechanisms in this region.

Physical Interpretation

The pattern is driven by well-understood climate feedbacks: 1) Surface albedo feedback (sea-ice and snow loss) drives the intense Arctic warming; 2) A slowdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) likely causes the reduced heat transport leading to the North Atlantic warming hole; 3) Differences in heat capacity and evaporative cooling limits result in faster warming over land than oceans.

Caveats

- The analysis relies on only two models (IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO), limiting the statistical robustness compared to a larger CMIP ensemble.

- The 10-year averaging period (2040–2049) is relatively short and may still contain signals from internal decadal variability (e.g., IPO, AMO) superposed on the forced trend.

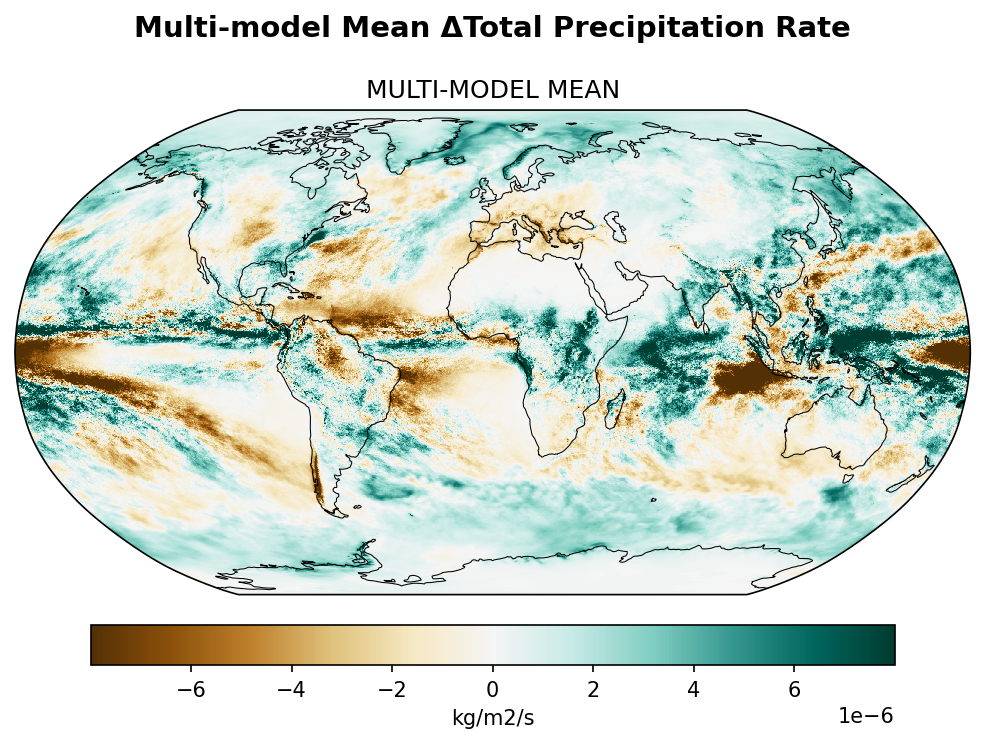

Multi-model Mean Total Precipitation Rate Change

| Variables | avg_tprate |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | kg/m2/s |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | Arithmetic mean of per-model (future − historical) differences. |

Summary medium

The figure illustrates the multi-model mean change in total precipitation rate (2040–2049 vs. 1990–2014) for the IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO models under the SSP3-7.0 scenario. The pattern broadly follows a 'wet-gets-wetter, dry-gets-drier' regime, featuring intensified equatorial precipitation, high-latitude wetting, and distinct drying over the Amazon and Mediterranean.

Key Findings

- Pronounced drying over the Amazon basin and Central America, with anomalies reaching -6e-6 kg/m²/s, indicating severe hydrological stress in these tropical forests.

- A sharp meridional dipole in the Tropical Pacific and Atlantic ITCZ regions, characterized by wetting along the equator and strong drying on the northern flanks (approx. 5°N–15°N), suggesting a narrowing or equatorward shift of the rain belts.

- Robust wetting signals in the high latitudes (Arctic and Southern Ocean) and the Horn of Africa, contrasting with significant drying in the Mediterranean basin and subtropical ocean gyres.

Spatial Patterns

The Tropical Pacific exhibits a distinct zonal wetting band along the equator, flanked by drying to the north and south, indicative of ITCZ intensification/narrowing. The Indian Ocean displays a zonal dipole pattern (wetter West, drier East/Maritime Continent). High latitudes (>50°) show widespread precipitation increases. Subtropical regions, particularly the Mediterranean, Southern Africa (west), and the Southeast Pacific, show coherent drying zones.

Model Agreement

The analysis is limited to two models (IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO) that share the same IFS atmospheric core. Consequently, the high spatial coherence likely reflects the specific sensitivity of the IFS physics package to SSP3-7.0 forcing, rather than a broad multi-model consensus. Differences in ocean resolution (FESOM vs NEMO) appear smoothed out in this mean, though the strong localized features (e.g., Gulf Stream extension) imply consistent eddy-permitting dynamics.

Physical Interpretation

The patterns are driven by a combination of thermodynamic and dynamic responses. Thermodynamically, specific humidity increases (Clausius-Clapeyron relation) enhance moisture convergence in the ITCZ and storm tracks (high-latitude wetting). Dynamically, the poleward expansion of the Hadley Cell contributes to subtropical drying (e.g., Mediterranean). The Amazon drying suggests a strengthening of subsidence or a shift in the South American Monsoon circulation, potentially amplified by land-surface feedbacks.

Caveats

- The ensemble consists of only two models sharing the same atmospheric component (IFS), significantly underestimating structural uncertainty compared to a full CMIP6 ensemble.

- The analysis period (2040–2049) is relatively short (10 years), meaning internal decadal variability (e.g., ENSO, PDO phases) could alias onto the forced climate change signal.

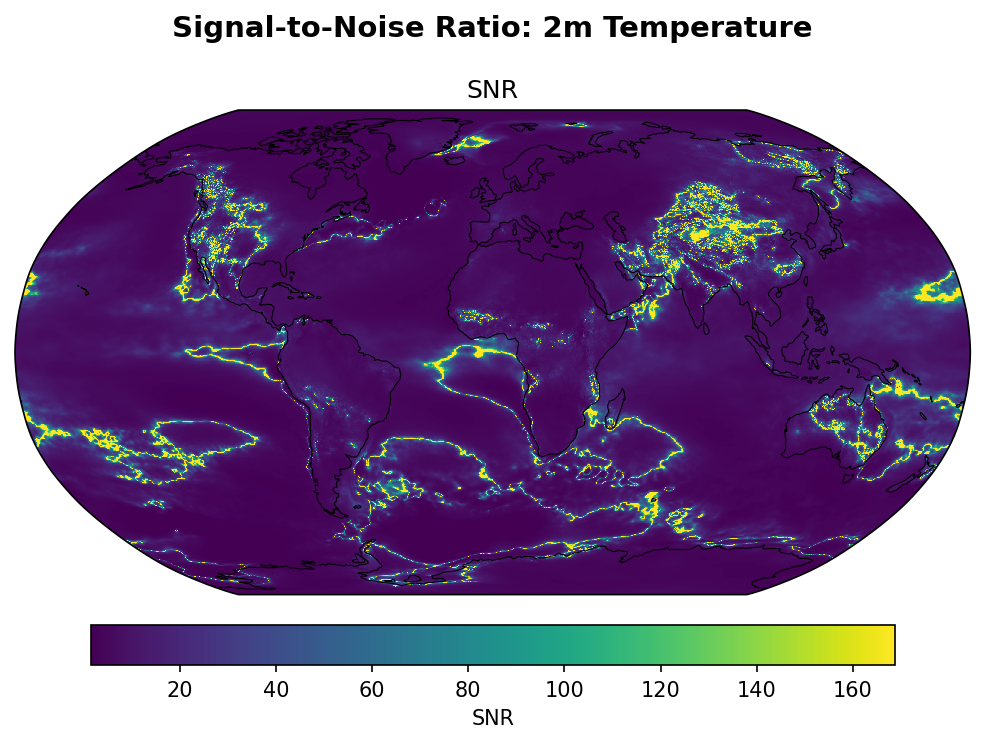

SNR 2m Temperature

| Variables | avg_2t |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | K |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | SNR = |multi-model mean| / inter-model std. |

Summary high

This figure maps the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of 2m temperature change (2040-2049 vs 1990-2014) derived from a comparison between the IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO coupled models. The map highlights a stark contrast between extreme model agreement over complex topography and coastlines versus relatively lower SNR ratios over the oceans and flat continental interiors.

Key Findings

- Extreme SNR values (>120) are strictly confined to major mountain ranges (Himalayas, Andes, Rockies) and coastlines, indicating near-perfect agreement between the two models in these regions.

- Oceanic regions generally display low SNR values (dark purple) compared to the orographic features, suggesting that differences in the ocean components (FESOM vs. NEMO) introduce significant variability in Sea Surface Temperature (SST) projections.

- Flat continental interiors (e.g., Amazon, Sahara, Australia) show much lower SNR than mountainous regions, implying that land-atmosphere feedbacks or advection from the differing oceans introduce divergence between the model configurations.

Spatial Patterns

The spatial distribution is dominated by topography. Bright yellow high-SNR structures perfectly trace the Tibetan Plateau, the Andes, the Rocky Mountains, the Alps, and the Ethiopian Highlands. Additionally, high SNR values outline continental coastlines globally. In contrast, the vast majority of the ocean basins and flat landmasses are rendered in dark purple, indicating significantly lower SNR ratios on this specific color scale.

Model Agreement

The models (IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO) show exceptionally high agreement (low inter-model standard deviation) over high-altitude terrain. This is likely because both models share the identical IFS atmospheric component and land-surface physiography; thus, the orographic forcing on temperature is treated identically. Disagreement is highest (lower SNR) over the oceans, reflecting the divergence between the unstructured mesh (FESOM) and structured grid (NEMO) ocean physics.

Physical Interpretation

The pattern indicates that the 2m temperature change signal is structurally locked by topography in the shared atmospheric model, leading to a vanishingly small denominator (standard deviation) and exploding SNR values over mountains. Over the oceans, the thermodynamic response is dependent on the specific ocean model dynamics (e.g., boundary currents, mixing), leading to larger inter-model differences. The coastline 'halo' effect likely results from consistent land-sea masking in the shared atmospheric grid dominating the signal.

Caveats

- The color bar range (0–165) is extremely wide; standard robust climate signals typically have an SNR > 1 or 2. Consequently, regions appearing 'dark' (low SNR) may still possess a statistically robust warming signal, but are visually dwarfed by the topographic outliers.

- Since only two models are compared, the 'noise' represents the difference between two realizations rather than a true multi-model ensemble spread.

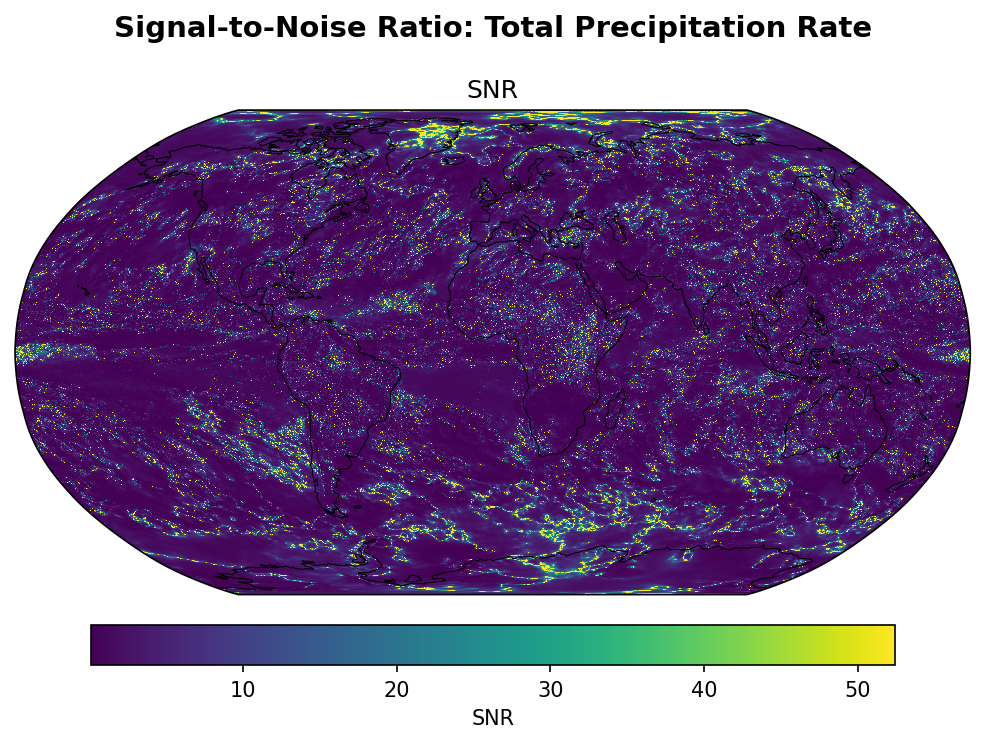

SNR Total Precipitation Rate

| Variables | avg_tprate |

|---|---|

| Models | ifs-fesom, ifs-nemo |

| Units | kg/m2/s |

| Baseline | 1990-2014 |

| Future | 2040-2049 |

| Method | SNR = |multi-model mean| / inter-model std. |

Summary medium

This diagnostic map illustrates the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of projected Total Precipitation Rate changes (2040-2049 vs 1990-2014) derived from two high-resolution coupled models (IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO) under the SSP3-7.0 scenario. The overall pattern reveals low SNR across the majority of the globe, implying that the difference between the two models (noise) often exceeds the magnitude of the mean projected change (signal), with robust signals confined to specific high-latitude and orographic regions.

Key Findings

- The majority of the global domain, particularly tropical and subtropical oceans, exhibits low SNR (< 10), indicating significant inter-model divergence regarding precipitation changes.

- Regions of high robustness (SNR > 30) are prominent in the Arctic Ocean and scattered areas of the Southern Ocean/Antarctic coast.

- Topographically complex regions, such as the Andes, Himalayas, and the Southern Alps of New Zealand, show high SNR values, suggesting consistent orographic forcing responses between the models.

Spatial Patterns

The map is dominated by low SNR values (dark purple/blue). High SNR values (yellow/green) form a coherent polar amplification pattern in the Arctic. In the mid-to-low latitudes, high SNR appears as 'speckled' noise primarily associated with major mountain chains or narrow frontal boundaries. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ) generally show low SNR, suggesting shifts in precipitation bands differ between the models.

Model Agreement

Agreement is strongest in the high latitudes, where the precipitation response is driven by robust large-scale thermodynamic constraints common to both models. Disagreement is highest in the tropics and dynamic ocean regions, where the distinct ocean components (FESOM vs. NEMO) likely generate differing Sea Surface Temperature (SST) gradients, shifting convective zones and degrading the SNR.

Physical Interpretation

The high SNR in the Arctic reflects the robust thermodynamic response to warming (Clausius-Clapeyron relation) and increased poleward moisture transport, a signal that overpowers internal variability and model differences. The high agreement over mountain ranges arises because both models share the same IFS atmospheric physics and high-resolution topography, forcing identical vertical motion and orographic precipitation. The low SNR in the tropics indicates that precipitation changes there are dynamically driven and highly sensitive to the structural differences in ocean coupling.

Caveats

- The analysis is based on only two models (IFS-FESOM and IFS-NEMO); 'inter-model standard deviation' in this context essentially measures the difference between these two realizations.

- The future integration period (2040-2049) is relatively short (10 years), meaning internal decadal variability likely contributes significantly to the 'noise', potentially masking the forced climate change signal.

- Precipitation is inherently spatially heterogeneous and noisy compared to temperature, naturally resulting in lower SNR values.